Can a machine really think? Is artificial intelligence the end of the human race or a tool that can aid us even after we die?

Professor Maggi Savin-Baden from the

School of Education discusses the role of artificial intelligence in digital immortality, virtual humans and what we can expect from the future.

Digital Immortality

The concept of digital immortality has emerged over the past decade and is defined in this post as the continuation of an active or passive digital presence after your death. This blog will explain how advances in knowledge management, machine to machine communication, data mining and artificial intelligence are now making an active presence after death possible. It will explain how digital immortality has moved beyond simple memorial pages and ‘beyond the grave’ updates, from dead family or friends. There are now companies dedicated to creating digitally immortal personas.

Given the range of practices and behaviours associated with digital immortality, there is evidence it is having an impact in religious contexts. For example, digital immortality is affecting grief and mourning practices. It is also creating new forms of legacy as well as introducing new issues for the funeral industry.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is often thought of as robots or thinking machines. From the popular point of view, artificial intelligence (AI) is seen as science-fiction characters like the Hal 9000 computer from 2001, or the androids from Channel 4’s Humans. In modern marketing terms, it is taken as any reasonably complex programme or algorithm – often based on machine-learning principles, yet the complexity and diversity of AI is much broader than this. Recently there have been considerable improvements to AI such as better text-to-speech, improved speech recognition and high-quality avatars (the bodily manifestation of one’s self).

The challenge with Artificial intelligence is to cross the ‘uncanny valley’; the idea that human replicas may elicit feelings of eeriness in looks, sound and especially behaviour, such as emotional responses. For example, virtual assistants such as Siri and Alexa provide voice and conversational interfaces to information and begin to deliver on some of the promises of virtual personal assistants. The growth in the use of machine learning techniques to mine large amounts of data and to make deductions from it that can equal (or even exceed) human analysis.

Hern reported that The European Parliament has urged the drafting of a set of regulations to govern the use and creation of robots and artificial intelligence.[i] The areas that need to be addressed are suggested to be:

- The creation of a European agency for robotics and AI;

- A legal definition of ‘smart autonomous robots’, with a registration for the most advanced;

- An advisory code of conduct to guide the ethical design, production and use of robots;

- A new reporting structure for companies requiring them to report the contribution of robotics and AI to the economic results of a company for the purpose of taxation and social security contributions

- A mandatory insurance scheme for companies to cover damage caused by their robots.

The report takes a special interest in the future of autonomous vehicles, such as self-driving cars, but as yet there seems relatively little detail about how this might be implemented or developed. However, in Autumn 2017 Sophia, a humanoid robot gave a speech at the United Nations, to prompt the recognition that there needs to be more debate, as well as legislation in this area.

Virtual Humans

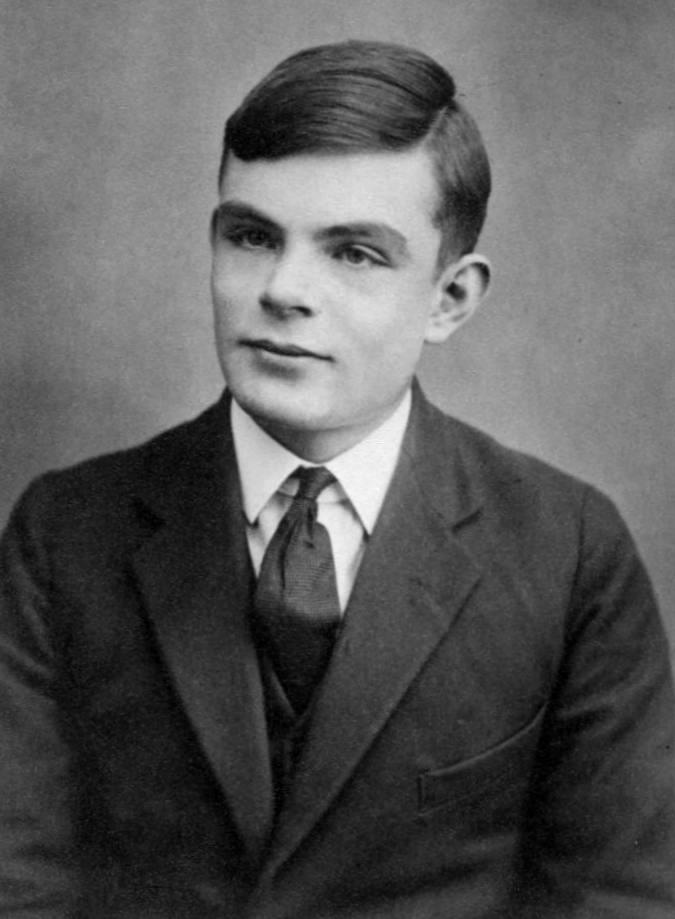

Alan Turing, who is widely considered to be the father of modern computer science and artificial intelligence.

Alan Turing, who is widely considered to be the father of modern computer science and artificial intelligence.

One of the main shifts has been to move away from a general understanding of AI and instead to refer to different types. One particular growth area is that of virtual humans. Turing suggested a test he called the ‘imitation game’, designed to answer the question ‘Can machines think?’[i] His prediction was that the test he proposed would be passed by about the year 2000, but this was not the case.

In the 1980s Searle suggested that the computer is just a symbol processing machine and it cannot be said to think.[i]

If a machine can play chess better than the very best human player, does that make it intelligent? Searle would claim no, that it is merely the human programmers that are intelligent, who have programmed the machine to implement their ideas. However, how is this different from a human mentor that teaches a student to play chess? Do we say the mentor is intelligent and the student is merely following the rules she was taught?

It is evident from the literature that ‘Virtual Humans’ tends to be used as an overarching term that includes Chatbots, Autonomous Agents and Pedagogical Agents. Virtual Humans are characters on the computer screen with embodied life-like behaviours such as speech, emotions, locomotion and gestures. Evidence has shown that many users are not only comfortable interacting with high-quality Virtual Humans, but that an emotional connection can be developed between users and as Virtual Humans. The focus is on enabling the user to interact with the software using everyday language rather than clicking on icons or using menu selections.

Many people are concerned about the impact and future of artificial intelligence. Whilst some of the worry is warranted, it is important to be aware of the ways in which media coverage can exaggerate claims.

There are legitimate concerns about artificial intelligence being used to control cars and weapons systems. However, it is probably unlikely that as Stephen Hawking suggests that ‘the development of full AI would spell the end of the human race.’

Conclusion

Not only are we seeing advances in knowledge management, data mining and artificial intelligence but also in merging our human bodies with technology. This ‘body hacking’ includes inserting chips into our arms to open doors and pick up metal objects, and implanting antenna into our brains to translate the colour spectrum into different vibrations, enabling the user to ‘hear’ colours. Whilst for some people this is seen as art, and for others as playing with technology, there are useful advances such as the creation of bone implants that enable the mounting of a replacement arm on to the skeleton which can then be controlled naturally, using brain signals.

[1] A. Hern, ‘Give robots “personhood” status, EU committee argues’ The Guardian 17th January (2017).

[1] A. Turing, ‘Computing machinery and intelligence’, Mind,LIX/236 (1950), pp. 433–460.

Professor Maggi Savin-Baden's research often focuses on innovation and change in learning, as well as virtual worlds and their role in teaching. Professor Savin-Baden has recently Co-authored a new book with David Burden on virtual humans called "Virtual Humans Today and Tomorrow" which explores virtual humans in a variety of roles, from personal assistants to teachers .

All views expressed in this blog are the Academic’s own and do not represent the views, policies or opinions of the University of Worcester or any of its partners.